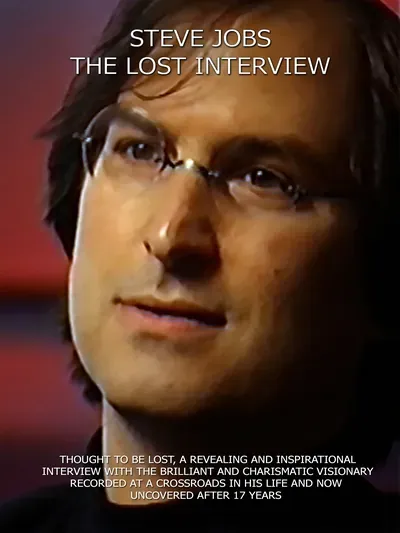

Steve Jobs The Lost Interview 1995 - Full Transcript and Highlights

Get this on Amazon

I’ve come across this interview of Steve Jobs in various small clips circulating the internet. But I never paid attention to watching it in its entirety. That is until Marty Cagan featured on Lenny’s Podcast and mentioned this interview.

I was blown away. This interview took place in 1995. How has he predicted the future of technology so well? How does he have timeless insights about (software and hardware) product development in 1995? Even before the boom of the internet?

I decided to watch this interview and share the transcript below. I’ve divided this transcript into topics. Feel free to jump to a topic that you find interesting. I do recommend watching the interview at least once. I’ve also highlighted parts that I found most interesting in bold below. These highlights are saved on my Readwise to help me get the most out of this talk.

If you’re short on time, jump straight to:

- On Xerox’s failure (ignoring the product people)

- On implementing vision and why some companies fail at it

- On execution and building a motivated team

If this theme of influence and execution resonates, my notes on 7 Rules of Power are a good follow-on read.

Introduction

Bob Cringely I’m Bob Cringely. Sixteen years ago, when I was making my television series, Triumph of the Nerds, I interviewed Steve Jobs. That was in 1995. Ten years earlier, Steve had left Apple, following a bruising struggle with John Sculley, the CEO he brought into the company. At the time of our interview, Steve was running NeXT, the niche computer company he founded after leaving Apple. Little did we know that within 18 months, he would sell NeXT to Apple, and six months later, he’d be running the place. The way things work in television, we used only a part of that interview in the series. And for years, we thought the interview was lost forever because the master tape went missing while being shipped from London to the US in the 1990s. Then, just a few days ago, series director Paul Sen found a VHS copy of that interview in his garage. There are very few TV interviews with Steve Jobs, and almost no good ones. They rarely show the charisma, candor, and vision that this interview does. And so, to honor an amazing man, here’s that interview in its entirety. Most of this has never been seen before.

Job’s entry into personal computers

Cringely: So how did you get involved with personal computers?

Jobs: Hmm. Well, um..I ran into my first computer when I was about 10 or 11. And it’s hard to remember back then. But I’m an old fossil now. I’m an old fossil. So when I was 10 or 11 was about 30 years ago. And no one had ever seen a computer. To the extent that they’d seen them in movies, and they were these big boxes with whirring..For some reason, they fixated on the tape drives as being the icon of what the computer was, or flashing lights somehow. And so nobody had ever seen one. They were very mysterious, very powerful things, that did something in the background. And so, to see one and actually get to use one was a real privilege back then. And I got into NASA, the Ames Research Center down here. I got to use a time-sharing terminal. So I didn’t actually see the computer, but I saw a time-sharing terminal. And in those days.. Again, it’s hard to remember how primitive it was. There was no such thing as a computer with a graphics video display. It was literally a printer. It was a teletype printer with a keyboard on it. And so you would keyboard these commands in, and then you would wait for a while, and the thing would go.. And it would tell you something out. But even with that, it was still remarkable, especially for a 10-year-old, that you could write a program in BASIC, let’s say, or FORTRAN. And actually, this machine would take your idea, and it would execute your idea and give you back some results. And if they were the results that you predicted, your program really worked. It was an incredibly thrilling experience. So, I became very captivated by a computer. And a computer, to me, was still a little mysterious,’cause it was at the other end of this wire, and I’d never really seen the actual computer itself. And then I got tours of computers after that, and saw the insides. And then I was part of this group at Hewlett-Packard. When I was 12, I called up Bill Hewlett, who lived in Hewlett-Packard at the time. And again, this dates me, but there was no such thing as an unlisted telephone number then. So I could just look in the book, and looked his name up. And he answered the phone, and I said, “Hi. My name’s Steve Jobs. You don’t know me, but I’m 12 years old, and I’m building a frequency counter, and I’d like some spare parts.” And so, he talked to me for about 20 minutes. I’ll never forget it as long as I live. And he gave me the parts, but he also gave me a job working at Hewlett-Packard that summer. And I was 12 years old then. And that really made a remarkable influence on me. Hewlett-Packard was really the only company I’d ever seen in my life at that age, and it formed my view of what a company was, and how well they treated their employees. They didn’t know about cholesterol back then. But at that time, they used to bring a big cartful of donuts and coffee out at 10 every morning. Everybody would take a coffee and donut break. And just little things like that, it was clear that the company recognized that its true value was its employees. So anyway, things led to things with Hewlett-Packard, and I started going up to their Palo Alto research labs every Tuesday night with a small group of people to meet some of their researchers and stuff, and I saw the first desktop computer ever made, which was the Hewlett-Packard 9100. It was about as big as a suitcase, but it actually had a small cathode-ray tube display in it, and it was completely self-contained. There was no wire going off behind the curtain somewhere. And I fell in love with it. And you could program it in BASIC and APL. And I would just, for hours, get a ride up to Hewlett-Packard and just hang around that machine and write programs for it. And so that was the early days. And I met Steve Wozniak around that time, too. Well, maybe a little earlier when I was about 14, 15 years old. And we immediately hit it off. He was the first person I’d met that knew more about electronics than I did, and so I was..I liked him a lot, and he was maybe five years older than I. He’d gone off to college and gotten kicked out for pulling pranks, and was living with his parents, and going to De Anza, the local junior college. So we became fast friends, and started doing projects together. We read about..We read about the story in Esquire magazine about this guy named Captain Crunch who could supposedly make free telephone calls. You’ve heard about this, I’m sure. And again, we were captivated. How could anybody do this? And we thought it must be a hoax. And we started looking through the libraries, looking for the secret tones that would allow you to do this. And it turned out, we were at Stanford Linear Accelerator Center one night, and way in the bowels of their technical library, way down at the last bookshelf, in the corner bottom rack, we found an AT&T technical journal that laid out the whole thing. And that’s another moment I’ll never forget. When we saw this journal, we thought, “My God! It’s all real.” And so, we set out to build a device to make these tones. And the way it worked was, you know when you make a long-distance call, you used to hear..(mimicking dial tones) Right? In the background? They were tones that sounded like the touch tone you could make on your phone, but they were a different frequency, so you couldn’t make them. It turned out that, that was the signal from one telephone computer to another controlling the computers in the network. And AT&T made a fatal flaw when they designed the original telephone network, digital telephone network, was they put the signaling from computer to computer in the same band as your voice, which meant that if you could make those same signals, you could put it right in through the handset. And literally, the entire AT&T international phone network would think you were an AT&T computer. So after three weeks we finally built a box like this that worked. And I remember, the first call we made was down to LA, one of Woz’s relatives down in Pasadena. We dialed the wrong number, but we woke some guy up in the middle of the night, and we were yelling at him like, “Don’t you understand we made this call for free?” And this person didn’t appreciate that. But it was miraculous, and we built these little boxes to do blue boxing, as it was called, and we put a little note in the bottom of them. Our logo was, “He’s got the whole world in his hands.” And they worked. We built the best blue box in the world. It was all digital. No adjustments. And so you could go up to a pay phone and you could take a trunk over to White Plains, and then take a satellite over to Europe, and then go to Turkey, take a cable back to Atlanta. And you could go around the world. You could go around the world five or six times ‘cause we learned all the codes for how to get on the satellites and stuff. And then, you could call the pay phone next door, and so you could shout in the phone, and after about a minute, it would come out the other phone. It was.. It was miraculous. And you might ask, “Well, what’s so interesting about that?” What’s so interesting is that we were young. And what we learned was that we could build something ourselves that could control billions of dollars’ worth of infrastructure in the world. That was what we learned, We didn’t know much. We could build a little thing that could control a giant thing. And that was an incredible lesson. I don’t think there would have ever been an Apple computer had there not been blue boxing.

Cringeley: Woz said you called the Pope?

Jobs: Yeah, we did call the Pope. He pretended to be Henry Kissinger. And we got the number of the Vatican, and we called the Pope. And they started waking people up in the hierarchy. I don’t know, cardinals and this and that. And they actually sent someone to wake up the Pope when, finally, we just burst out laughing, and they realized that we weren’t Henry Kissinger. Yeah, and so, we never got to talk to the Pope, but it was very funny.

Cringeley: So..So the jump from blue boxes to personal computers, what sparked that?

Jobs: Well..Necessity, in the sense that there was time-sharing computers available, and there was a time-sharing company in Mountain View that we could get free time on. So, uh.. But we needed a terminal, and we couldn’t afford one, so we designed and built one. And that was the first thing we ever did. We built this terminal. And so, what an Apple I was, was really an extension of this terminal putting a microprocessor on the back end. That’s what it was. So first we built the terminal, and then we built the Apple I. And we really built it for ourselves because we couldn’t afford to buy anything. And we’d scavenge parts here and there and stuff, and we’d build these all by hand. They’d take 40 to 80 hours to build one, and then they’d always be breaking cause there’s all these tiny little wires. And so, it turned out, a lot of our friends wanted to build them, too. And although they could scavenge most of the parts as well, they didn’t have the skills to build them that we had acquired by training ourselves through building them. And so, we ended up helping them build most of their computers, and it was really taking up all of our time. And we thought if we could make what’s called a printed circuit board, which is a piece of fiberglass with copper on both sides that’s etched to form the wires so that you could build a computer..You could build an Apple I in a few hours instead of 40 hours. If we only had one of those, we could sell them to all our friends for as much as it cost us to make them, and make our money back. And everybody would be happy, and we’d get a life again. So we did that. I sold my Volkswagen Bus, and Steve sold his calculator, and we got enough money to pay a friend of oursto make the artwork to make a printed circuit board. And we made some printed circuit boards, and we sold some to our friends. And I was trying to sell the rest of them, so that we could get our Microbus and calculator back. And I walked into the first computer store in the world which was the Byte Shop of Mountain View, I think, on El Camino. It metamorphosized into an adult bookstore a few years later. But at this point, it was the Byte Shop. And the person that ran it, I think his name was Paul Terrell, he said, “I’ll take 50 of those.” I said, “This is great.” He said, “But I want them fully assembled.” We’d never thought of this before. So we then kicked this around, we thought, “Why not? Why not try this?” And so, I spent the next several days on the phone talking with electronics parts distributors. We didn’t know what we were doing. And we said, “Look, here’s the parts we need. “We figured we’d buy 100 sets of parts, build 50, sell them to the Byte Shop for twice what it cost us to build them, therefore paying for the whole 100, and then we’d have 50 left, and we could make our profits by selling those. So we convinced these distributors to give us the parts on net 30 days credit. We had no idea what that meant. “Net 30? Sure.” “Sign here.” And then, so we had 30 days to pay them. And so we bought the parts, we built the products, and we sold 50 of them to the Byte Shop in Palo Alto, and got paid in 29 days. And then went and paid off the parts people in 30 days, and so we were in business. But we had the classic Marxian profit realization crisis, in that our profit wasn’t in a liquid currency, our profit was in 50 computers sitting in the corner. So then, all of a sudden, we had to think,”Wow! How are we going to realize our profit?” And so we started thinking about distribution, “Are there any other computer stores?” And we started calling the other computer storesthat we’d heard of across the country, and we just eased into business that way.

On Mike Markkula’s investment in Apple

Cringeley: The third key figure in the creation of Apple was former Intel executive Mike Markkula. I asked Steve how he came aboard.

Jobs: We were designing the Apple II, and we really had much higher ambitions for the Apple II. Woz’s ambitions were, he wanted to add color graphics. My ambition was that..It was very clear to me that while there were a bunch of hardware hobbyists that could assemble their own computers or at least take our board and add the transformers for the power supply, and the case and the keyboard, et cetera, and go get the rest of the stuff. For every one of those, there were a thousand people that couldn’t do that, but wanted to mess around with programing. Software hobbyists. Just like I had been when I was 10, discovering that computer. And so my dream for the Apple II was to sell the first real packaged computer. Packaged personal computer where you didn’t have to be a hardware hobbyist at all. And so, combining both of those dreams, we actually designed the product. And I found a designer, and we designed the packaging and everything, and we wanted to make it out of plastic, and we had the whole thing ready to go. But we needed some money for tooling the case and things like that. We needed a few hundred thousand dollars. And this was way beyond our means, so I went looking for some venture capital. And I ran across one venture capitalist named Don Valentine who came over to the garage. And he later said I looked like a renegade from the human race. That was his famous quote. And he said he wasn’t willing to invest in us, but he recommended a few people that might, and one of them was Mike Markkula. So I called Mike on the phone, and Mike came over, and Mike had retired at about 30 or 31 from Intel. He was a product manager there and had gotten a little bit of stock, and made, like, a million bucks on stock options, which at that time, was quite a lot of money. And he’d been investing in oil and gas deals, and staying home and doing that sort of thing. And he, I think, was kind of antsy to get back into something, and Mike and I hit it off very well. And so Mike said, “Okay, I’ll invest after a few weeks.” And I said, “No. No. We don’t want your money. We want you.” So we convinced Mike to actually throw in with us as an equal partner. And so Mike put in some money, and Mike put in himself, and we took this design that was virtually done with the Apple II, and tooled it up and announced it a few months later at the West Coast Computer Faire.

Cringeley: What was that like?

Jobs: It was great. We got the best. The West Coast Computer Faire was small at that time, but to us, it was very large. And so, we had this fantastic booth there. We had a projection television showing the Apple II, and showing its graphics, which today, look very crude, but at that time, were, by far, the most advanced graphics on a personal computer. And I think..My recollection is, we stole the show. And a lot of dealers and distributors started lining up, and we were off and running.

The thinking behind running a succesful company

Cringeley: How old were you?

Jobs: 21.

Cringeley: You’re 21, you’re a big success. You’ve just done it by the seat of your pants. You don’t have any particular training in this. How do you learn to run a company?

Jobs: Throughout the years in business, I found something, which was, I’d always ask why you do things. And the answers you invariably get are,”Oh, that’s just the way it’s done.” Nobody knows why they do what they do. Nobody thinks about things very deeply in business. That’s what I found. I’ll give you an example. When we were building our Apple Is’ in the garage, we knew exactly what they cost. When we got into a factory in the Apple II days, the accounting had this notion of a standard cost, where you’d set a standard cost, and at the end of a quarter, you’d adjust it with a variance. And I kept asking, “Well, why do we do this?”And the answer was, “Well, that’s just the way it’s done.”And after about six months of digging into this, what I realized was, the reason you do it is because you don’t really have good enough controls to know how much it costs, so you guess, and then you fix your guess at the end of the quarter, and the reason you don’t know how much it costs is because your information systems aren’t good enough. But nobody said it that way. And so, later on, when we designed this automated factory for Macintosh, we were able to get rid of a lot of these antiquated concepts and know exactly what something cost to the second. So in business, a lot of things are.. I call it folklore. They’re done because they were done yesterday and the day before. And so what that means is, if you’re willing to ask a lot of questions and think about things and work really hard, you can learn business pretty fast. It’s not the hardest thing in the world. It’s not rocket science.

On why everyone should learn programming

Cringeley: Now, when you were first coming in contact with these computers and inventing them, and before that, working on the HP 9100, you talked about writing programs. What sort of programs? What did people actually do with these things?

Jobs: Hmm..See, what we did with them..Well, I’ll give you a simple example. When we were designing our blue box, we wrote a lot of custom programs to help us design it, and to do a lot of the dog work for using terms of calculating master frequencies with sub divisors to get other frequencies and things like that. We used the computer quite a bit. And to calculate how much error we would get in the frequencies, and how much could be tolerated. So, we used them in our work. But much more importantly, it had nothing to do with using them for anything practical. It had to do with using them to be a mirror of your thought process, to actually learn how to think. It was, I think, the greatest value of learning how to..I think everybody in this country should learn how to program a computer, should learn a computer language, because it teaches you how to think. It’s like going to law school. I don’t think anybody should be a lawyer, but I think going to law school would actually be useful ‘cause it teaches you how to think in a certain way. In the same way that computer programing teaches you, in a slightly different way, how to think. And so, I view computer science as a liberal art. It should be something that everybody learns. Takes a year in their life, one of the courses they take is learning how to program.

Cringeley: Yeah, but I learned APL, which, obviously, is part of the reason why I’m going through life sideways.

Jobs: You look back and consider itan enriching experience that taught you to think in a different way, or not?

Cringeley: Uh, no. Not that particularly. Other languages perhaps more so, but I started with APL.

On what its like to get rich

Cringeley: So, obviously, the Apple II was a terrific success. Just incredibly so. And the company grew like Topsy, and eventually went public, and you guys got really rich. What’s it like to get rich?

Jobs: It’s very interesting. I was worthabout over $1 million when I was 23, and over $10 million when I was 24, and over $100 million when I was 25. And it wasn’t that important because I never did it for the money. I think money is a wonderful thing because it enables you to do things. It enables you to invest in ideasthat don’t have a short-term payback and things like that. But especially at that point in my life, it was not the most important thing. The most important thing was the company, the people, the products we were making, what we were gonna enable people to do with these products, so I didn’t think about it a great deal. I never sold any stock. Just really believed that the company would do very well over the long term.

The unforgettable visit to the Xerox PARC

Cringeley: Central to the development of the personal computer was the pioneering work being done at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center which Steve first visited in 1979.

Jobs: I had 3-4 people who kept bugging me that I ought to get my rear over to Xerox PARC and see what they were doing, and so I finally did. I went over there. And they were very kind, and they showed me what they were working on, and they showed me, But I was so blinded by the first one that One of the things they showed me was object-oriented programing. They showed me that, but I didn’t even see that. The other one they showed me was, really, a network computer system. They had over 100 Alto computers, all networked, using email, et cetera, et cetera. I didn’t even see that. I was so blinded by the first thing they showed me, which was the graphical user interface. I thought it was the best thing I’d ever seen in my life. Now, remember, it was very flawed. What we saw was incomplete. They’d done a bunch of things wrong, but we didn’t know that at the time. But still, though, they had..The germ of the idea was there and they’d done it very well. And within 10 minutes, it was obvious to me that all computers would work like this someday. It was obvious. You could argue about how many years it would take, you could argue about who the winners and losers might be, but you couldn’t argue about the inevitability. It was so obvious. You would have felt the same way had you been there.

Cringeley:Those are the exact words that Paul Allen used. It’s really interesting. You saw it, then you brought some people back with you? And what happened the next time? They made you cool your heels for a while?

Jobs: No.

Cringeley: No? Well, Adele Goldberg says otherwise. And she said that she argued against doing it for 3 hours and they took you other places and showed you other things while she was arguing.

Jobs: Oh! Oh! You mean they were reluctant to show us the demo?

Cringeley: She was.

Jobs: Oh, okay. Well, I have no idea. But they did show us. So..And it’s good that they showed us, because the technology crashed and burned at Xerox.

Cringeley: Yeah, why?

On Xerox’s failure (ignoring the product people)

Jobs: Oh, I actually thought a lot about that. And I learned more about that with John Sculley later on, and I think I understand it now pretty well. What happens is, like with John Sculley..John came from PepsiCo, and they, at most, would change their product once every 10 years. To them, a new product was, like, a new-size bottle, right? So if you were a product person, you couldn’t change the course of that company very much. So who influenced the success of PepsiCo? The sales and marketing people. Therefore, they were the ones that got promoted, and therefore, they were the ones that ran the company. Well, for PepsiCo, that might have been okay. But it turns out, the same thing can happen in technology companies that get monopolies. Like, oh, IBM and Xerox. If you were a product person at IBM or Xerox..So you make a better copier or a better computer. So what? When you have a monopoly market share, the company is not any more successful. So the people that can make the company more successful are sales and marketing people, and they end up running the companies. And the product people get driven out of the decision-making forums. And the companies forget what it means to make great products. The product sensibility and the product genius that brought them to that monopolistic position gets rotted out by people running these companies who have no conception of a good product versus a bad product. They have no conception of the craftsmanship that’s required to take a good idea and turn it into a good product. And they really have no feeling in their hearts usually about wanting to really help the customers. So that’s what happened at Xerox. The people at Xerox PARC used to call the people that ran Xerox “toner heads.”And they just had..These toner heads would come out to Xerox PARC, and they just had no clue about what they were seeing. Toner is what you put into a copier. The toner that you add to an industrial copier. So basically, they were copier he.. The people at Xerox PARC used to call the people that ran Xerox “toner heads.”And they just had..These toner heads would come out to Xerox PARC, and they just had no clue about what they were seeing. Toner is what you put into a copier. The toner that you add to an industrial copier. So basically, they were copier heads that just had no clue about a computer or what it could do. And so they just grabbed defeat from the greatest victory in the computer industry. Xerox could have owned the entire computer industry today. Could have been a company 10 times its size. Could have been IBM. Could have been the IBM of the ’90s. Could have been the Microsoft of the ’90s. So..But anyway, that’s all ancient history. It doesn’t really matter anymore.

Cringeley: Sure. You mentioned IBM. When IBM entered the market, was that a daunting thing for you at Apple?

Jobs: Oh, sure. Here was Apple, a one-billion-dollar company. And here was IBM, at that time, probably about 30-some-odd-billion-dollar company entering the market. Sure, it was. It was very scary. We made a very big mistake, though. IBM’s first product was terrible. It was really bad. And we made a mistake of not realizing that a lot of other people had a very strong vested interest in helping IBM make it better. So if it had just been up to IBM, they would have crashed and burned. But IBM did have, I think, a genius in their approach, which was to have a lot of other people have a vested interest in their success. And that’s what saved them in the end.

On implementing vision and why some companies fail at it

Cringeley: So you came back from visiting Xerox PARC with a vision. And how did you implement the vision?

Jobs: Well, I got our best people together and started to get them working on this. The problem was that we’d hired a bunch of people from Hewlett-Packard. And they didn’t get this idea. They didn’t get it. I remember having dramatic arguments with some of these people who thought the coolest thing in user interface was soft keys at the bottom of a screen. They had no concept of proportionally-spaced fonts, no concept of a mouse. As a matter of fact, I remember arguing with these folks, people screaming at me that it would take us five years to engineer a mouse and it would cost $300 to build. And I finally got fed up. I just went outside and found David Kelley Design, and asked him to design me a mouse. And in 90 days, we had a mouse we could build for 15 bucks that was phenomenally reliable. So I found that, in a way, Apple did not have the caliber of people that was necessary to seize this idea in many ways. And there was a core team that did, but there was a larger team that mostly had come from Hewlett-Packard that didn’t have a clue.

Cringeley: Well, there comes this issue of professionalism. There is a dark side and a light side to it, isn’t there?

Jobs: Well, no. You know what it is? No, it’s not dark and light. It’s that people get confused. Companies get confused. When they start getting bigger, they want to replicate their initial success. And a lot of them think, “Well, somehow there is some magic in the process of how that success was created.” So they start to try to institutionalize process across the company. And before very long, people get very confused that the process is the content. And that’s, ultimately, the downfall of IBM. IBM has the best process people in the world. They just forgot about the content. And that’s what happened a little bit at Apple, too. We had a lot of people who were great at management process. They just didn’t have a clue as to the content. And in my career, I found that the best people are the ones that really understand the content, and they’re a pain in the butt to manage. But you put up with it because they’re so great at the content. And that’s what makes great products. It’s not process. It’s content. So we had a little bit of that problem at Apple. And that problem eventually resulted in the Lisa, which had its moments of brilliance. In a way, it was very far ahead of its time, but there wasn’t enough fundamental content understanding. Apple drifted too far away from its roots. To these Hewlett-Packard guys, $10,000 was cheap. To our market, to our distribution channels, $10,000 was impossible. So we produced a product that was a complete mismatch for the culture of our company, for the image of our company, for the distribution channels of our company, for our current customers. None of them could afford a product like that. And it failed.

Cringeley: Now you and John Couch fought for leadership of the Lisa. How did that come about?

Jobs: Absolutely, and I lost. Well, I thought Lisa was in serious trouble. I thought Lisa was going off in this very bad direction as I’ve just described. And I could not convince enough people in the senior management of Apple that that was the case and we ran the place as a team for the most part. So I lost. And at that point in time.. I brooded for a few months. But it was not very long after that that it really occurred to me that if we didn’t do something here..The Apple II was running out of gas, and we needed to do something with this technology fastor else Apple might cease to exist as the company that it was. And so I formed a small team to do the Macintosh, and we were on a mission from God to save Apple. No one else thought so, but it turned out we were right. And as we evolved the Mac, it became very clear that this was also a way of reinventing Apple. We reinvented everything. We reinvented manufacturing. I visited probably 80 automated factories in Japan, and we built the world’s first automated computer factory in the world in California here. So we adopted the 68,000 microprocessor that Lisa had. We negotiated a price that was a fifth of what Lisa was going to pay for it because we were going to use it in much higher volume. And we really started to design this product that could be sold for $1,000 called the Macintosh. And we didn’t make it. We could have sold it at $2,000. Although, we came out at $2,500. And we spent four years of our life doing that. We built the product. We built the automated factory, the machine to build the machine. We built a completely new distribution system. We built a completely different marketing approach. And I think it worked pretty well.

On execution and building a motivated team

Cringeley: Now, you motivated this team. You had to guide them. Build the team, motivate it, guide them, deal with them. We’ve interviewed just lots and lots of people from your Macintosh team. And what it keeps coming down to is your passion, your vision, and..How do you order your priorities in there? What’s important to you in the development of a product?

Jobs: You know..One of the things that really hurt Apple was after I left, John Sculley got a very serious disease, and that disease.. I’ve seen other people get it, too. It’s the disease of thinking that a really great idea is 90% of the work, and that if you just tell all these other people, “Here is this great idea,” then, of course, they can go off and make it happen. And the problem with that is that there is just a tremendous amount of craftsmanship in between a great idea and a great product. And as you evolve that great idea, it changes and grows. It never comes out like it starts because you learn a lot more as you get into the subtleties of it, and you also find there is tremendous tradeoffs that you have to make. There are just certain things you can’t make electrons do. There are certain things you can’t make plastic do or glass do or factories do or robots do. And as you get into all these things, designing a product is keeping 5,000 things in your brain, these concepts, and fitting them all together and continuing to push to fit them together in new and different ways to get what you want. And every day you discover something new, that is a new problem or a new opportunity to fit these things together a little differently. And it’s that process that is the magic. And so we had a lot of great ideas when we started. But what I’ve always felt, that a team of people doing something they really believe in is like..When I was a young kid, there was a widowed man that lived up the street. And he was in his 80s. He was a little scary-looking. And I got to know him a little bit. I think he might have paid me to mow his lawn or something. And one day, he said, “Come on into my garage. I want to show you something.” And he pulled out this dusty, old rock tumbler. It was a motor and a coffee can and a little band between them. And he said, “Come on with me.” We went out to the back and we got just some rocks. Some regular, old, ugly rocks. And we put them in the can with a little bit of liquid and a little bit of grit powder. And we closed the can up, and he turned this motor on, and he said, “Come back tomorrow.” And this can was making a racket as the stones went around. And I came back the next day, and we opened the can, and we took out these amazingly beautiful polished rocks. The same common stones that had gone in, through rubbing against each other like this, creating a little bit of friction, creating a little bit of noise, had come out these beautiful polished rocks. And that’s always been, in my mind, my metaphor for a team working really hard on something they’re passionate about is that it’s through the team, through that group of incredibly talented people, bumping up against each other, having arguments, having fights sometimes, making some noise, and working together, they polish each other and they polish the ideas, and what comes out are these really beautiful stones. So it’s hard to explain, and it’s certainly not the result of one person. People like symbols, so I’m the symbol of certain things. But it really was a team effort on the Mac. Now, in my life, I observed something fairly early on at Apple, which..I didn’t know how to explain it then, but I’ve thought a lot about it since. Most things in life, the dynamic range between average and best is at most 2-1. If you go to New York City, and you get an average taxicab driver versus the best taxicab driver, you’re probably going to get to your destination with the best taxicab maybe 30% faster. In an automobile, what’s the difference between average and the best? Maybe 20%. The best CD player and an average CD player? I don’t know. 20%. 2-1 is a big dynamic range in most of life. In software, and it used to be the case in hardware, too, the difference between average and the best is 50-to-1, maybe 100-to-1. Very few things in life are like this. But what I was lucky enough to spend my life in, is like this. And so I’ve built a lot of my success off finding these truly gifted people, and not settling for B and C players but really going for the A players, and I found something. I found that when you get enough A players together, when you go through the incredible work to find five of these A players, they really like working with each other because they’ve never had a chance to do that before. And they don’t want to work with B and C players. And so it becomes self-policing, and they only want to hire more A players, and so you build up these pockets of A players, and it propagates. And that’s what the Mac team was like. They were all A players. And these were extraordinarily talented people.

Cringeley: But they’re also people who now say that they don’t have the energy anymore to work for you.

Jobs: Sure. Oh, I think if you talk to a lot of people on the Mac team, they will tell you it was the hardest they’ve ever worked in their life. Some of them will tell you that it was the happiest they’ve ever been in their life. But I think all of them will tell you that is certainly one of the most intense and cherished experiencesthey will ever have in their life. You know, it’s..Some of those things are not sustainable for some people.

On giving feedback to the team

Cringeley: What does it mean when you tell someone their work is shit?

Jobs: It usually means their work is shit. Sometimes, it means, “I think your work is shit, and I’m wrong.” But usually, it means their work is not anywhere near good enough.

Cringeley: I had this great quote from Bill Atkinson who says, when you say someone’s work is shit, you really mean, “I don’t quite understand it. Would you please explain it to me?” Jobs: No, that’s not usually what I meant. When you get really good people, they know they’re really good, and you don’t have to baby people’s egos so much, and what really matters is the work. And everybody knows that. That’s all that matters is the work. People are being counted on to do specific pieces of the puzzle. And the most important thing, I think, you can do for somebody who is really good and who’s really being counted on is to point out to them when their work isn’t good enough. And to do it very clearly and to articulate why, and to get them back on track. And you need to do that in a way that does not call into question your confidence in their abilities, but leaves not too much room for interpretation that the work that they have done for this particular thing is not good enough to support the goal of the team. And that’s a hard thing to do. And I’ve always taken a very direct approach. And I think if you talk to people that have worked with me, the really good people have found it beneficial. Some people have hated it. And I’m also one of these people that I don’t really care about being right. I just care about success. So, you’ll find a lot of people that will tell you that I had a very strong opinion and they presented evidence to the contrary, and five minutes later, I completely changed my mind. Because I’m like that. I don’t mind being wrong. I’ll admit that I’m wrong a lot. It doesn’t really matter to me too much. What matters to me is that we do the right thing.

Apple’s entry into desktop publishing

Cringeley: So how and why did Apple get into desktop publishing which would become the Mac’s killer app?

Jobs: I don’t know if you know this, but we got the first Canon laser printer engine shipped in the United States at Apple, and we had it hooked up to a Lisa, actually imaging pages before anybody. Before HP. Long before HP, long before Adobe. But I heard a few times, people would tell me, “Hey, there are these guys over in this garage that left Xerox PARC. You ought to go see them.” And I finally went and saw them, and I saw what they were doing, and it was better than what we were doing. And they were gonna be a hardware company. They wanted to make printers and the whole thing. And so I talked them into being a software company. And we had canceled our internal project. And a bunch of people wanted to kill me over this, but we did it. And I had cut a deal with Adobe to use their software, and we bought 19.9% of Adobe at Apple. They needed some financing. We wanted a little bit of control. And we were off to the races, and so we got the engines from Canon. We designed the first laser printer controller at Apple. And we got the software from Adobe, and we introduced the LaserWriter. And no one at the company wanted to do it but a few of us in the Mac group. Everybody thought a $7,000 printer was crazy. What they didn’t understand was you could share it with AppleTalk. They understood it intellectually, but they didn’t understand it viscerally because the last really expensive thing we tried to sell was Lisa. So we pushed this thing through. And I had to basically do it over a few dead bodies, but we pushed this thing through, and it was the first laser printer on the market, as you know, and the rest is history. When I left Apple, Apple was the largest printer company measured by revenue in the world. It lost that distinction to Hewlett-Packard after I left, unfortunately. But when I left, it was the largest printer company in the world.

Cringeley: Did you envision desktop publishing? Was that a no-brainer?

Jobs: You know..Yes. But.. We also envisioned really a networked office. And so, in January of 1985, when we had our annual meeting and introduced our new products, I made probably the largest marketing blunder of my career by announcing the Macintosh Office instead of just desktop publishing. And we had desktop publishing as a major component of that, but we announced a bunch of other stuff as well, and I think we should have just focused on desktop publishing at that time.

On the departure from Apple

Cringeley: After serious disagreements with Apple CEO John Sculley, Steve left the company in 1985. Tell us about your departure from Apple.

Jobs: Oh, it was very painful. I’m not even sure I want to talk about it. What can I say? I hired the wrong guy (Sculley). And he destroyed everything I’d spent 10 years working for. Starting with me, but that wasn’t the saddest part. I would have gladly left Apple if Apple would have turned out like I’d wanted it to. He basically got on a rocket ship that was about to leave the pad. And the rocket ship left the pad. And it kind of went to his head. He got confused, and thought that he built the rocket ship. And then he changed the trajectory so that it was inevitably going to crash into the ground.

Cringeley: But it was always the..In the pre-Macintosh days, and the early Macintosh days, it was always the Steve and John show. the hip for a while there. And then something happened to split you. What was that catalyst?

Jobs: Well, what happened was that the industry went into a recession in late 1984. Sales started seriously contracting. And John didn’t know what to do. He had not a clue. And there was a leadership vacuum at the top of Apple. There were fairly strong general managers running the divisions. I was running the Macintosh division, somebody else was running the Apple II division, et cetera. There were some problems with some of the divisions. There was a person running the storage division that was completely out to lunch. And a bunch of things that needed to be changed. But all those problems got put in a pressure cooker because of this contraction in the market place. And there was no leadership. John was in a situation where the board was not happy and where he was probably not long for the company. And one thing I did not ever see about John until that time was he had an incredible survival instinct. Somebody once told me, “This guy didn’t get to be the president of PepsiCo without these kinds of instincts.” And it was true. And John decided that a really good person to be the root of all these problems would be me. And so, we came to loggerheads. And John had cultivated a very close relationship with the board. And they believed him. So, that’s what happened.

Cringeley: So there were competing visions for the company?

Jobs: Oh, clearly. Well, not so much competing visions for the company, ‘cause I don’t think John had a vision for the company.

Cringeley: Well, I guess I’m asking, what was your vision that lost out in this instance?

Jobs: It wasn’t an issue of vision. It was an issue of execution. In the sense that my belief was that Apple needed much stronger leadership, to unite these various factions that we had created with the divisions, that the Macintosh was the future of Apple, that we needed to rein back expenses dramatically in the Apple II area, that we needed to be spending very heavily in the Macintosh area. Things like that. And John’s vision was that he should remain the CEO of the company. And anything that would help him do that would be acceptable. I think that Apple was in a state of paralysis in the early part of 1985. And I wasn’t, at that time, capable, I don’t think, of running the company as a whole. I was 30 years old. And I don’t think I had enough experience to run $2billion company. Unfortunately, John didn’t either. So anyway, I was told, in no uncertain terms, that there was no job for me. It would have been far smarter for Apple to let me work on the next..I volunteered. I said, “Why don’t I start a research division?” And give me a few million bucks a year and I’ll go hire some really great people. “We’ll do the next great thing.” And I was told there was no opportunity to do that. So, my office was taken away. It was.. I’ll get real emotional if we keep talking about this. Anyway.. But that’s irrelevant. I’m just one person, and the company was a lot more people than me. So that’s not the important part. The important part was the values of Apple over the next several years were systematically destroyed.

Cringeley: I then asked Steve for his thoughts on the state of Apple. Remember, this was 1995, a year before he would go back to Apple. Remember, too, that when Apple bought NeXT a year after this interview, Steve immediately sold the Apple stock he received as part of the sale.

Jobs: Apple’s dying today. Apple’s dying a very painful death. It’s on a glide slope to die. And the reason is because..When I walked out the door at Apple, we had a 10-year lead on everybody else in the industry. Macintosh was 10 years ahead. We watched Microsoft take 10 years to catch up with it. Well, the reason that they could catch up with it was because Apple stood still. The Macintosh that’s shipping today is 25% different than the day I left. They’ve spent hundreds of millions of dollars a year on R&D. A total of, probably, $5 billion on R&D. What did they get for it? I don’t know. But it was..What happened was the understanding of how to move these things forward and how to create these new products somehow evaporated. And I think a lot of the good people stuck around for a while. But there wasn’t an opportunity to get together and do this ‘cause there wasn’t any leadership to do that. So, what’s happened with Apple now is that they’ve fallen behind in many respects, certainly in market share. And most importantly, their differentiation has been eroded by Microsoft. And so, what they have now is, they have their installed base. Which is not growing, and which is shrinking slowly, but will provide a good revenue stream for several years. But it’s a glide slope that’s just gonna go like this. So, it’s unfortunate. And I don’t really think it’s reversible at this point in time.

On Microsoft

Cringeley: What about Microsoft? That’s the juggernaut now. And it’s a Ford LTD going into the future. It’s definitely not a Cadillac. It’s not a BMW. It’s just..What’s going on there? How did those guys do that?

Jobs: Well, Microsoft’s orbit was made possible by a Saturn V booster called IBM. And I know Bill would get upset with me for saying this, but of course it was true. And much to Bill and Microsoft’s credit, they used that fantastic opportunity to create more opportunity for themselves. Most people don’t remember, but until 1984 with the Mac, Microsoft was not in the applications business. It was dominated by Lotus. And Microsoft took a big gamble to write for the Mac. And they came out with applications that were terrible. But they kept at it and they made them better, and eventually, they dominated the Macintosh application market. And then used a springboard of Windows to get into the PC market with those same applications. And now they dominate the applications in the PC space, too. characteristics. I think they’re very strong opportunists, and I don’t mean that in a bad way. Japanese. They just keep on coming. They were able to do that because of the revenue stream from the IBM deal. But nonetheless, they made the most of it, and I give them a lot of credit for that. The only problem with Microsoft is they just have no taste. They have absolutely no taste. And what that means is..I don’t mean that in a small way, I mean that in a big way. In the sense that…they don’t think of original ideas and they don’t bring much culture into their product. And you say, “Well, why is that important?” Well, proportionally-spaced fonts come from typesetting and beautiful books. That’s where one gets the idea. If it weren’t for the Mac, they would never have that in their products. And so, I guess I am saddened, not by Microsoft’s success. I have no problem with their success. They’ve earned their success for the most part. I have a problem with the fact that they just make really third-rate products. Their products have no spirit to them. Their products have no spirit or enlightenment about them. They are very pedestrian. And the sad part is that most customers don’t have a lot of that spirit either. But the way that we’re going to ratchet up our species is to take the best and to spread it around to everybody, so that everybody grows up with better things and starts to understand the subtlety of these better things. And Microsoft’s just.. It’s McDonald’s. So that’s what saddens me. Not that Microsoft has won, but that Microsoft’s products don’t display…more insight and more creativity.

On the origins of NeXT

Cringeley: So, what are you doing about it? Tell us about NeXT.

Jobs: Well, I’m not doing anything about it. Because NeXT is too small of a company to do anything about that. I’m just watching it. And there is really nothing I can do about it.

Cringeley: Next, we talked about NeXT, the company Steve was running in 1995 which Apple was soon to buy. NeXT software would become the heart of the Mac in the form of OS X.

Jobs: Well, maybe the best thing, since we don’t have much time, is I just tell you what NeXT is today. The innovation in the industry is in software. And there hasn’t ever been a real revolution in how we created software. Certainly not in the last 20 years. Matter of fact, it’s gotten worse. While the Macintosh was a revolution for the end user to make it easier to use, it was the opposite for the developer. The developer paid the price. And software got much more complicated to write as it became easier to use for the end user. So, software is infiltrating everything we do these days. In businesses, software is one of the most potent competitive weapons. The most successful business war was MCI’s Friends and Family in the last 10 years. And what was that? It was a brilliant idea and it was custom billing software. AT&T didn’t respond for 18 months, yielding billions of dollars’ worth of market share to MCI, not because they were stupid but because they couldn’t get the billing software done. So in ways like that and smaller ways, software is becoming an incredible force in this world. To provide new goods and services to people, whether it’s over the Internet or what have you. Software is going to be a major enabler in our society. We have taken another one of those brilliant original ideas at Xerox PARC that I saw in 1979, but didn’t see really clearly then, called object-oriented technology. And we have perfected it and commercialized it here and become the biggest supplier of it to the market. And this object technology lets you build software 10 times faster and is better. And so that’s what we do. And we’ve got a small-to- medium-sized business and we’re the largest supplier of objects. We’re a 50-to-75-million-dollar company. Got about 300 people. And that’s what we do.

Vision for Web

Cringeley: The end of the third show, actually is the one moment where we do look into the future..as Channel 4 has asked us to do that. And so what’s your vision of 10 years from now with this technology that you’re developing?

Jobs: Well, I think the Internet and the Web.. in software and in computing today. I think one is objects, but the other one is the Web. The Web is incredibly exciting because it is the fulfilment of a lot of our dreams that the computer would ultimately not be primarily a device for computation but metamorphosize into a device for communication. And with the Web, that’s finally happening. And secondly, it’s exciting because Microsoft doesn’t own it, and therefore, there’s a tremendous amount of innovation happening. So I think that the Web is going to be profound in what it does to our society. As you know, about 15% of the goods and services in the US are sold via catalogs or over the television. All that is gonna go on the Web and more. Billions and billions. Soon tens of billions of dollars’ worth of goods and services are gonna be sold on the Web. A way to think about it is that it is the ultimate direct-to-customer distribution channel. Another way to think about it is the smallest company in the world can look as large as the largest company in the world on the Web. So I think the Web..As we look back 10 years from now, the Web is going to be the defining technology. The defining social moment for computing. And I think it’s going to be huge. I think it’s breathed a whole new generation of life into personal computing. And I think it’s going to be huge. Just forget about what we’re doing. Just as an industry, the Web is gonna open a whole new door to this industry.

Cringeley: And it’s another one of those things that it’s obvious once it happens, but five years ago, who would have guessed?

Jobs: Right. That’s right. Isn’t this a wonderful place we live in?

Talking about his passion

Cringeley: I was keen to know about Steve’s passion. What drove him?

Jobs: I read an article when I was very young in Scientific American, and it measured the efficiency of locomotion for various species on the planet. So for bears and chimpanzees and raccoons and birds and fish. How many kilocalories per kilometer did they spend to move?And humans were measured, too. And the condor won. It was the most efficient. And mankind, the crown of creation, came in with a rather unimpressive showing about a third of the way down the list. But somebody there had the brilliance to test a human riding a bicycle. Blew away the condor. All the way off the charts. And I remember, this really had an impact on me. I really remember this that humans are tool builders, and we build tools that can dramatically amplify our innate human abilities. And to me..We actually ran an ad like this very early at Apple. The personal computer was the bicycle of the mind. And I believe that with every bone in my body that of all the inventions of humans, the computer is going to rank near, if not at, the top as history unfolds and we look back. And it is the most awesome tool that we have ever invented, and I feel incredibly lucky to be at exactly the right place in Silicon Valley, at exactly the right time, historically, where this invention has taken form. And as you know, when you set a vector off in space, if you can change its direction a little bit at the beginning, it’s dramatic when it gets a few miles out in space. I feel we are still, really, at the beginning of that vector. And if we can nudge it in the right directions, it will be a much better thing as it progresses on. I think we’ve had a chance to do that a few times, and it brings all of us associated with it tremendous satisfaction.

Cringeley: But how do you know what’s the right direction?

Jobs: Ultimately, it comes down to taste. It comes down to taste. It comes down to trying to expose yourself to the best things that humans have done, and then try to bring those things into what you are doing. Picasso had a saying. He said, “Good artists copy. Great artists steal.” And we have always been shameless about stealing great ideas. And I think part of what made the Macintosh great was that the people working on it were musicians and poets and artists and zoologists and historians who also happened to be the best computer scientists in the world. But if it hadn’t been for computer science, these people would have all been doing amazing things in life in other fields. And they brought with them, we all bought to this effort, a very liberal arts air, a very liberal arts attitude that we wanted to pull in the best that we saw in these other fields into this field. And I don’t think you get that if you’re very narrow.

On being a hippie

Cringeley: One of the questions I asked everyone in the series was,”Are you a hippie or a nerd?” Jobs: Oh, if I had to pick one of I’m clearly a hippie. All the people I worked with were clearly in that category, too.

Cringeley: Really? Why? Do you seek out hippies, or are they attracted to you?

Jobs: Well, ask yourself, “What is a hippie?” This is an old word that has a lot of connotations, but to me, ‘cause I grew up..Remember that the ’60s happened in the early ’70s, right? So we have to remember that. And that’s sort of when I came of age, so I saw a lot of this. And a lot of it happened right in our backyard here. So, to me, the spark of that was that there was something beyond what you see every day. There is something going on here in life..Beyond just a job, and a family, and there is something more going on. There is another side of the coin that we don’t talk about much, and we experience it when there’s gaps, when we just aren’t really..When everything is not ordered and perfect, when there is a gap, you experience this inrush of something. And a lot of people have said all throughout history, you find out what that was. Whether it’s Thoreau, or whether it’s some Indian mystics, or whoever it might be, and the hippie movement got a little bit of that, and they wanted to find out what that was about, and that life wasn’t about what they saw their parents doing. And of course, the pendulum swung too far the other way, and it was crazy, but there was a germ of something there. And it’s the same thing that causes people to wanna be poets instead of bankers. And I think that’s a wonderful thing. And I think that that same spirit can be put into products, and those products can be manufactured and given to people, and they can sense that spirit. If you talk to people that use the Macintosh, they love it. You don’t hear people loving products very often. Really. But you could feel it in there. There was something really wonderful there. So, I don’t think that most of the really best people that I’ve worked with have worked with computers for the sake of working with computers. They’ve worked with computers because they are the medium that is best capable of transmitting some feeling that you have, that you want to share with other people. And before they invented these things, all these people would have done other things. But computers were invented, and they did come along, and all these people did get interested in school or before school, and said, “Hey, this is the medium that I think I can say something in.”

Conclusion

In 1996, a year after this interview, Steve Jobs sold NeXT to Apple. He then took control of his old company at a time when it was 90 days from bankruptcy. What followed was a corporate renaissance unparalleled in American business history. With innovative products like iMac, iPod, iTunes, iPhone, iPad, and Apple Stores, Jobs turned an almost bankrupt Apple into the most valuable company in America. As he said in this interview, he took the best and spread it around ‘so that everybody grows up with better things’.

Want to add a quick comment? (optional)